Lifter profiles

part one

part two

part three

For those of you who have not heard of Maxick, I'll let the numbers speak for themselves.

At a height of 5' 3 1/4'' and a weight 'that never exceeded 147 pounds' (Willoughby):

Right hand military press 112lb

Right hand snatch 165lb

Right hand jerk (shouldered with both hands) 240lb

Two hands military press 230lb

Two hands continental press 254lb

Two hands clean and jerk 272 1/2lb

Two hands continental jerk 340lb

Moreover, Maxick was known for his skill at muscle control, tremendous grip and wrist strength, handbalancing ability, and gymnastics feats--he was capable of holding an iron cross on a pair of chains, and walking up and down stairs on his hands. He thickened his abdominals, too, to the point that he could lie on the ground and have his 185-pound sponsor Tromp Van Diggelen jump onto his stomach from the top of a seven-foot ladder.

Training these abilities gave him a very thickly developed and powerful build. As someone said of tremendous powerlifter Lamar Gant, "he's really big for such a little guy" (or something to that affect) and that can definitely be applied to Maxick:

There's a big difference between Maxick's '145 pounds' and mine....

Also, it should be noted that Maxick performed all the above lifts in competition, with the strictest of form--thus, the distinction between the military and continental presses. Given the judging of competitions at the time, we can assume that he pressed out some of his jerks, however, there is no doubt that he performed his presses without any side or back bend.

Max Sick was born to Swiss parents in Munich in 1882, and raised by his mother and a German stepfather after his own father died at a very young age (thus making Max a naturalized German citizen). He was exceedingly sickly growing up, afflicted with dropsy, rickets, and lung problems (Tyrrell).

Through years of isometric training, muscle control, eventually progressing to handbalancing and gymnastics, an engineering job, and eventually weightlifting training; Max transformed himself from a very small and sickly boy into what can be described as nothing other than a all-around powerhouse the likes of which have rarely been seen in the history of strength and physical culture.

In his early twenties, Max abandoned a potential career in engineering to pursue something that would enable him to further develop himself full time, in addition to studying philosphy on the side. He started working as an artists' model, a circus performer (he was both a top-mounter and an under-stander--it was virtually unheard of for such a small man to be the 'bottom' in a hand to hand balancing act, but Maxick was strong enough to do so) and developed solo acts of his own. He also changed his name to a one-word 'Maxick' because he thought it would appeal more to English audiences--at least, that was Tromp Van Diggelen's explanation.

Maxick holding a perfect front lever on parallel bars at age 52

Most of Maxick's act consisted of muscle control, isolating and controlling individual muscles in specific patterns. This was much more sophisticated than the routines of today's bodybuilders, involving, among other things, unilateral flexing of muscle groups, and a high level of scapular and abdominal control. In addition to being able to 'roll' his stomach muscles, Maxick could flex individual rows, both vertical and horizontal. [Maxick's original instructive book. Muscle Control, is available online in a number of places. Beware the man-ass, though....] Maxick did much of this 'muscle control' to music, as Sandow had done, but by all acounts, with a greater degree of control! He also performed a rings routine holding onto a pair of chains, thus displaying his gripping power, and often lifted audience members overhead. According to many accounts, he would take up a 200 pound man, side press him with one hand, and then walk off stage still holding the man overhead. He trained extensively with barbells in various athletic clubs, but did little if any weight lifting in his performances.

Now, on to Maxick's workouts. Most sources are content to state that 'he did a lot of muscle control, and apparently did handbalancing and lifted weights at some point' but I found a routine he laid out in one of his books--Great Strength by Muscle Control--that he himself used indefinitely. From what I've read, most of the 'old timers' did not do a lot of 'program hopping'; they either found a routine that they liked and followed for the majority of their career, or else did not have a routine at all. Any and all experimentation or play was done after the scheduled lifting.

His training advice--"Never attempt a record oftener than twice weekly. Rest from the weights for two consecutive days, attempting the record on the third day. On the day that the record is attempted, keep off the legs as much as possible before lifting. Try to beat a previous record by a pound at a time--it is by far the surer way. When other exercises are performed, go through them after the lifting. Only practice the lifts at which you wish to excel, or those at which you are particularly good."

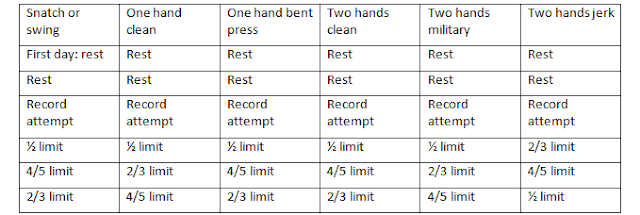

Maxick's training routine for the aforementioned lifts:

As you can see, it is a six-day rotation, with two off days, one heavy day, one light day, and two moderate days for each lift. The numbers listed are the top attempt for the day, and all lifts would be done with singles (sets of one repetition). As he wrote, all other training was done after the days' lifting. For him, this would be handbalancing, muscle control, and gymnastics.

It is worth mentioning that Sig Klein and Ike Berger, also absurdly strong lightweights, used similar training layouts--a heavy day, two or three light to moderate days, and follow the lifting (all or almost all singles) with bodybuilding or bodyweight strength training.

In addition to the above routine, Maxick listed these standards for each of the lifts--

Clean (split style--also, Maxick apparently did these with relatively little knee dip, so basically a power clean. He never squat cleaned, in fact I am not sure if any lifters did at this time. For weights he could not power clean, he continentalled them to his shoulders): 1.75x bodyweight

Military press: 1.5x bodyweight

One arm military press: 0.66x bodyweight (remember, no side or back lean here, heels together, two-second pause before pressing)

Continental press: 1.75x bodyweight (back bend and a split stance allowed)

One arm jerk: 1.33x bodyweight

Bent press (a lift Maxick did not practice, he believed it relied too much on technique): 1.75x bodyweight

One arm snatch: 1x bodyweight

One arm swing: 1x bodyweight (both done squat-style)

Maxick at the bottom of a one arm swing. Note the unreal upper back and shoulder development, the result of years of heavy one or two armed pulls from the floor, heavy overhead pressing, and gymnastics.

Maxick had the following advice for technique in the various lifts (from How to Become a Great Athlete and Great Strength by Muscle Control):

"...The single handed clean to shoulder may be performed in a variety of ways... do not forget to use a bar that is slightly bend, and turn the bend away from you before lifting, so that as soon as the bar leaves the ground it turns into the palm of the hand.... In both the single and double handed clean pull in [racking the bar on the shoulders] success depends not so much upon the pull as upon the speed with which the elbow or elbows can be whipped under the bar, and it is this part of the lift that should be borne in mind, as the pull can be done mechanically. Do not be misled by any rubbish about pulling slowly at first; this may suit a tall weak man with a spring bar, but it won't suit men who have to create records."

Maxick performing one of his favorite stunts: side press a man while holding a beer in his other hand--without spilling a single drop. Tromp Van Diggelen claimed that Maxick could side press him (185 pounds) 16 times in this manner.

Some other advice:

-Maxick said that in both one and two arm jerks, the initial drive should get the bar at least to forehead level.

-He advised a split stance for the continental press, and to bend the front knee slightly as to get into a better position (like a standing high incline press) without straining the back.

-For the one arm military press, he noted that "if the bell be pressed to the side, the body must go out of the correct position." Translation: do not push your elbow out to the side. Do not kick your hip out. Keep your body straight, your elbow forwards, and press straight up. [Yes, this is very hard. Try it--and you'll see just how impressive the military presses of some of these guys were!]

-As far as body tension goes, he noted that "when the bell has gone up a certain distance it usually seems to stick... were [the lifter] to exercise patience and keep still doggedly controlling the muscles and tightening up the weak places, he would frequently turn apparent failure to success."

-Finally, as far as form went: "...hardly two men perform these lifts alike. These lifts should be analysed and studied with weights that are well within your power, and the positions best suited to your physique discovered."

Most of that is pretty good advice even for trainees today. As you can see, Maxick's analytical approach to technique, conservative progressions, and hard, steady work for years paid off with his transformation from a weak boy to one of the all around strongest men ever at 150 pounds. As David Willoughby wrote, "of him, it could almost be said 'We shall not see his like again'. At least during the period of 60 years that has passed since Maxick was in his prime, no other man of his weight has equaled him."

Sources/further reading:

Willoughby, David. 'The Super-Athletes'.

Maxick. 'Muscle Control.'

Maxick. 'Great Strength by Muscle Control.'

Maxick. 'How to Become a Great Athlete.'

Van Diggelen, Tromp. 'Maxick--a Superman!'

Tyrrell, Ron. 'Marvelous Max--the Story of Maxick.'

As always--I hope you enjoyed the blog entry! Ask any questions in the comments section below, or send me an email: affectinggravity@gmail.com. The next one will be either another about program design, or the next in the 'simple progressions' series, a bit more about tweaks for Bryce Lane's 50/20....

Amazing gem, amazing man

ReplyDeleteI'm reading the book and it's really humbling how little control I have over my own body

ReplyDelete